- We have a massive sale right now on the Close Combat franchise and Distant Worlds 2, now is a great time to check out these titles

If you have an interest in pike and shot, we have several excellent titles covering the epochs covered in this article. Fields of Glory II: Medieval, Pike and Shot, and Sengoku Jidai are all excellent titles for wargaming with the medieval and early modern pikeman.

Welcome back to the Armory, where we will cover part 2 of our article on pikes. Last time we looked at the pikemen of antiquity that fought with Philip and Alexander. With the victory of the Roman legions, the pike mostly disappeared for over a millennia from the Mediterranean. They finally made a big return in the high middle ages and the Renaissance, re-emerging in both Scotland, Switzerland, and Flanders.

With the fall of the Western Roman Empire a mounted Germanic warrior aristocracy came to govern most of western Europe. This new aristocracy developed a feudal form of government (feudal is a loaded word in historical studies, but we won't wage that battle here) where military service was owed by nobles to the King. This new system of government was decentralized, agrarian, and built on relationships of personal patronage. The resulting armies were small, cavalry dominated, and only capable of taking to the field for short wars.

The personal oath of fealty to a feudal overlord defined the political relationships of the middle ages

There were, as always in history, plenty of exceptions to this model, often resulting from climate and material culture. The British isles and the low countries had strong traditions of militia service and infantry-centric warfare, as did northern Italy. These militia armies frequently fought as formations of spearmen and skirmishers. They were armed and armored in a mix of whatever the locals could bring together from their personal property. They formed up and fought in the style of the local cultural military tradition, rather than any doctrine set by a monarch. Culture isn’t static though, weapons and tactics did gradually evolve and change.

Italian communal militia could defeat Imperial armies composed of knights, such as at the Battle of Legnano

The Scottish Schiltron was initially a static defensive spear formation. At Falkirk these spear men defeated English cavalry in the open field, but suffered tremendous casualties from English longbow fire. Later at Bannockburn, pike-armed Schiltrons demonstrated the ability to fight offensively when drilled properly and formed into rectangular/linear formations. The pike’s chief utility was that it gave infantry the capacity to defeat a charge by fully armored knights. Defeating a charge was not guaranteed, but the reach and the massed ranks of pike points made victory far more likely.

Bannockburn saw an army of Scottish pikemen and cavalry defeat a numerically superior English force

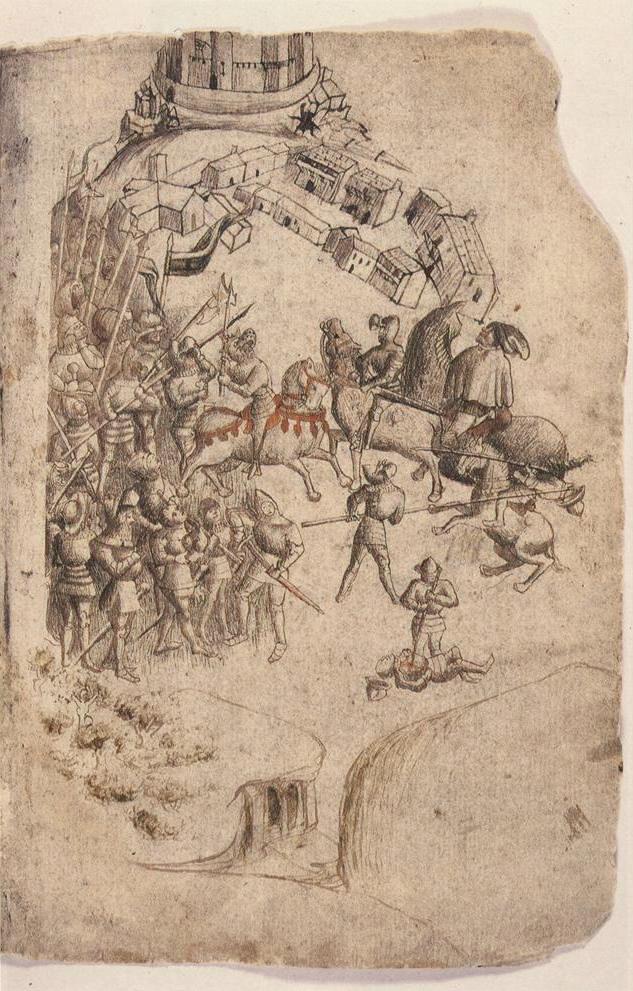

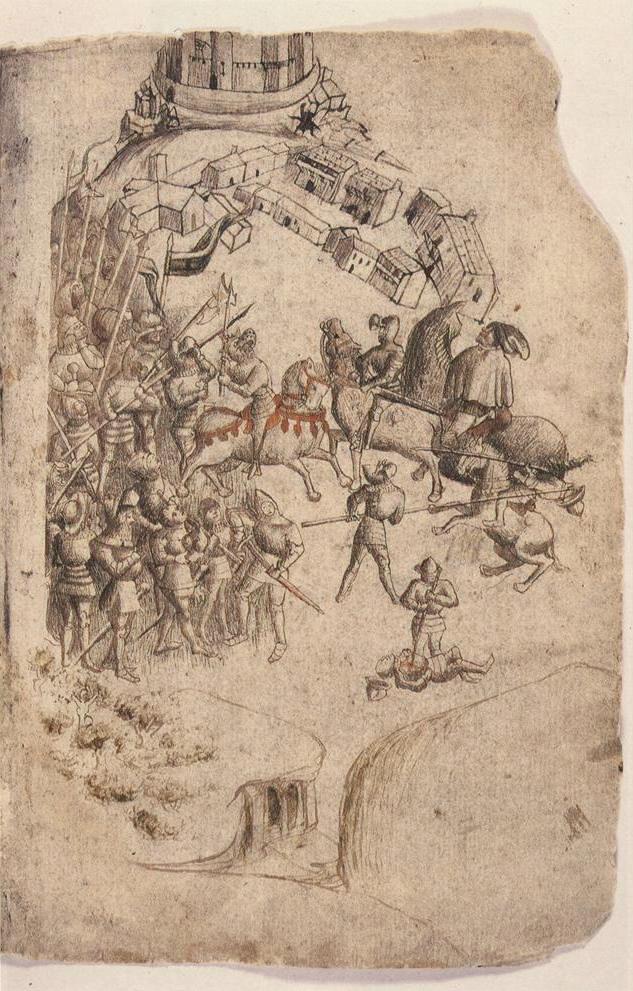

In Flanders the Flemish militia fielded formations of pikemen that, under the right circumstances, could defeat well trained and well equipped knights. At the Battle of the Golden Spurs in 1302 a mix of pikemen, crossbowmen, and goedendag-armed militia defeated a French army of mounted men-at-arms. This combined formation hinted at the eventual composition of the pike formations of the renaissance and early-modern period.

An illustration from the Courtrai Chest of the Flemish miltia, armed with pikes and Goedendag

The Swiss, organized in a confederation of fiercely independent cities and towns, had developed their militia into deep columns of pike-armed infantry. These columns were aggressive, trained and organized to rapidly close into melee. The Swiss gained fame as mercenaries, and became the premier infantry of the 15th century. In the battles of Grandson, Morat, and Nancy, Swiss pikemen decisively defeated the well-trained armies of Charles the Bold, breaking the power of the Duchy of Burgundy. The resulting prestige lead to a proliferation of Swiss mercenaries across Europe. This did a great deal to spread the pike as the premier battlefield weapon.

Compared to antiquity, these new pike formations differed from phalanxes. The old Macedonian Phalanx was composed of 256 men formed to fight entirely to the front. They were also protected with small shields strapped to their left arm, so both hands were free to use their pike. The Swiss pike block was far larger, often numbering in the thousands. If flanked in open country the men were trained to form a kind of hedgehog formation to defend the flanks and rear of the column. Halberdiers and later, the Zweihander-armed Doppelsoldner, were heavily armored and equipped with shorter and more agile weapons. They could respond to flankers or work their way into an enemy formation by getting inside and between the enemie’s pikes. While unwieldy to turn, a Swiss pike block could advance and attack rapidly if properly formed.

Doppelsoldners were also armed as handgunners in the early 16th century

The push-of-pike was what occurred when two pike blocks charged into one-another. In the event that neither force broke and ran before contact, the pikemen would gradually close with one another. Pressure from behind would turn the fight at the front into a crush as these two bristling hedgehogs stabbed and jostled with one-another. Doppelsoldners would then try to break into the enemies formation. These pushing matches would see the ugliest kind of bloody attritional fighting, until one side gave way and broke. At that point the pursuit of the routing enemy formation would often see a one-sided massacre and slaughter.

The push of pike could turn into a bloody, indecisive quagmire

The late 15th and 16th centuries saw a proliferation of firearms. At their debut, black powder weapons were primarily useful for sieges. Cannons were far too heavy and handgonnes were often too awkward and unreliable for battlefield use. Gradually these weapons, along with the more traditional crossbow, underwent refinement as metallurgy and designs improved. These improved missile weapons like the black powder arquebus, windlass crossbow, or lighter field artillery pieces all made the killing power of missile weapons far more effective on the battlefield. This did not immediately revolutionize warfare, but did stimulate the evolution of more complex formations.

A 19th century illustration of a handgunner with a rest, early handguns were heavy and required a fork to help stabilize the barrel

The recovery from the collapse of the Roman Empire was a gradual process. The initial feudal regimes were capable of mobilizing limited manpower and resources for their wars. As cities and trade networks recovered from their low point in the dark ages, the feudal state was capable of mustering far more men and material as they tapped the wealth of these new towns. Privileges were granted, monopoly charters were sold, and wealthy burghers were given access to the halls of aristocratic power and privilege in exchange for fiscal backing of military campaigns.

For example in 1415 at the Battle of Agincourt, conservative estimates have the English at around 6,000-8,000 effectives, with the French at 14,000-15,000 effectives, ignoring servants and those in the luggage train. At the Battle of Pavia, a little over a century later, the French could put 26,000 professional mercenaries and men-at-arms in the field, while the Habsburgs could put 28,000 men in the field. These men could be paid for thanks to an increasingly sophisticated fiscal system that often left King and Emperor in massive debt.

Agincourt is arguably one of the last great battles of the middle age, before the transition to what we call the Renaissance and early modernity

The growth of professional armies, the re-introduction of the pike to European warfare, and the increasing effectiveness of missile weapons made combined arms essential. The long reloading time of a handgun made missile troops vulnerable to the mounted man-at-arms. The pikeman, formed in a dense block and relatively unarmored, was vulnerable to missile fire and incapable of pursuing skirmishers. The solution found was the Tercio, a mixed formation of pikemen and arquebusiers. The pikeman could ward off cavalry charges and engage other infantry, while crossbowmen and arquebusiers could pour fire into the enemy from relative safety, sheltered by this massive pike block.

Emperor Maximillian frequently campaigned to expand the holdings of the Habsburg family, these costly wars were made possible by securing loans from...

The Tercio was built like a bastion. Organized around a central pike block, arquebusiers were concentrated on the four corner points of the formation, capable of pouring fire in any direction. Over time as firearms continued to improve, the ratios of a Tercio shifted away from the pike and in favor of the arquebusiers and musketeer. By the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) these formations were increasingly linear and dominated by firearms. Rather than an all-round defensive pike block, many armies adopted simpler formations of a central, thinner block of pikemen with musketeers on either flank. These shallower formations allowed fire to be concentrated to the front. Augmented with lighter artillery and field guns battles were increasingly decided by fire, rather than the push of pike or shock of a cavalry charge.

...Jakub Fugger, an exceptionally wealthy gold miner and banker, whose financing played a major role in the rise of the Habsburg Empire

This kind of pike and shot warfare remained mostly confined to Europe, but similar combinations did appear in east Asia. Both the Ming dynasty, the Daimyo warlords of Japan, and the Korean Joseon dynasty would create some kind of spear/pike and firearms formations. These formations would be organized differently than European ones, conforming to local geographic political conditions. The refinements of firearms and artillery and their global proliferation often stimulated military reforms. Oda Nobunaga encouraged the adoption of firearms in his army, and famously equipped his Ashigaru (peasant soldiers) with a longer Yari (spear) that approached pike length.

A samurai general armed with a yari oversees the assault on Nagashino castle

The pike of the middle ages and early modern period is thus married to firearms and missile weapons, you can’t really talk about one without the other. The whole period of early modern warfare is often summarized and described as “Pike and Shot” for good reason. The defensive Scottish schiltron was shot to pieces at Falkirk, and so the pike block was refined to be far more aggressive and eventually integrated missile troops directly into the formation. Firearms eventually became deadly enough that pike’s were done away with entirely. The invention of the socket bayonet allowed an entire infantry force to be armed with firearms and still be equipped with a melee weapon with the reach of a spear.

Early modern warfare at the tactical level is a long process of the deep, attacking pike column transforming into the linear formations of the 18th century. Warfare is never static and is always undergoing some kind of evolutionary process. It’s very seldom a single discrete weapon is invented that “changes everything”. The atom bomb might be the one example where that rings true. In the case of the pike, this massive weapon defined by it’s reach and unwieldiness, it almost seems to evolve back into the smallest and most discrete of weapons, the knife. Your 21st century infantryman is more likely to use his bayonet as a utility knife than to repel an enemy cavalry charge, but there is a strange shared tradition here that goes back all the way to the pikemen of the 15th century.

Until next time, have fun out there, and keep your flanks secure.