Representing history as accurately as possible while maintaining playability has been crucial to giving players the authentic feel of 1930s China.

Politics in China at this time was steeped in betrayals, double-dealings, and political intrigue—perhaps more so than in any other major country involved in World War II. And yes, I do consider the 1937–1941 phase of the Second Sino-Japanese War to be part of World War II.

While I’ll cover the political and diplomatic aspects of the war—and how they intersected with military operations—in the 1937 Marco Polo to Pearl Harbor Strategy Guide, this Developer Diary focuses on how I modeled the Chinese major ground armies.

THE REPUBLIC OF CHINA

The National Revolutionary Army

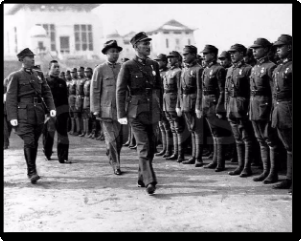

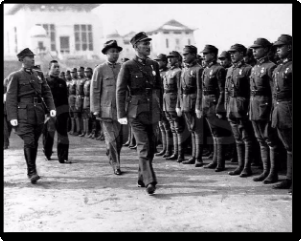

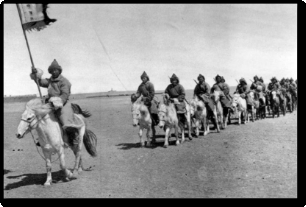

China entered the war with several distinct military factions, each with its own level of effectiveness and loyalty. While Chiang Kai-shek was the internationally recognized leader of the Republic of China and head of the ruling Kuomintang, his control over the military was far from absolute. Despite his apparent success in unifying China through force, many units within the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) remained more loyal to their original regional warlords than to Chiang’s central government.

At its core, the NRA consisted of Chiang’s Central Army, which included a handful of Elite Divisions, and a large number of forces aligned with provincial warlords. Loyalty and quality varied widely across these formations.

On paper, China had over one million men under arms in 1937, organized into roughly 170 divisions. Of these:

-

About 80 divisions were loyal to Chiang and part of the Central Army.

-

Roughly 20 divisions were considered elite—trained and partially equipped by the German military mission.

-

Approximately 70 divisions remained under the control of provincial warlords, whose loyalty to the central government was often limited or conditional.

The Central Army

Led by Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, the Central Army was the largest and most organized Chinese force in the NRA at the outbreak of war. This is reflected in the game by giving China the greatest number and variety of units for the Allied side. The Chinese player can deploy or build over 85 units, including a limited number of tanks and artillery.

However, the Central Army—and even more so the provincial warlord forces—faced serious challenges. Most units were poorly equipped, relying on outdated weapons with limited access to tanks and artillery. Training was inconsistent, logistics were weak and internal divisions and corruption further degraded operational effectiveness, and many of the mechanics of the Strategic Command game engine have been used to model these limitations.

The most significant changes implemented were to the offensive and defensive values of Chinese units relative to their Japanese counterparts. It is overwhelmingly agreed upon by historians that the Japanese Army outclassed the Chinese in terms of tactics, equipment, and training. In game terms, that meant the Chinese had to be numerically inferior on a unit-for-unit basis.

For example, a Chinese Army Group (equivalent to a Western "Army" with 50,000–90,000 soldiers) has only 75–90% of the offensive and defensive values of a Japanese Division, which typically fielded around 20,000 troops. The disparity is even more pronounced for Chinese Army units (roughly equivalent to a Western "Corps" with 15,000–30,000 soldiers), which range from 30–65% of a Japanese Division's combat effectiveness.

To visually emphasize this asymmetry, I also implemented an aesthetic solution: Chinese Army Groups use a 4-soldier bitmap icon, while Japanese units use a 2-soldier icon. This creates a visual impression that a smaller Japanese force is exerting outsized impact against a much larger but weaker Chinese force.

The Central Army also fielded a number of effective guerrilla operations that caused the Japanese some tactical if not strategic dilemmas. Both Chinese and Provincial guerrillas will activate as the game progresses.

The Elite Divisions

The German-trained divisions of the NRA are critical to any early success the Chinese player can achieve. In-game, these elite units are deployed at the player’s discretion, allowing for flexibility in how they support your overall strategy. Once on the field, they will be the most effective Chinese units available for countering Japanese advances.

An elite Chinese division can almost go toe-to-toe with a Japanese division, boasting around 80–90% of the offensive and defensive values of its Japanese counterpart. However, they must be skillfully managed and carefully integrated with other Chinese unit types to blunt Japanese offensives effectively. Used recklessly or in isolation, even these elite formations can be overwhelmed.

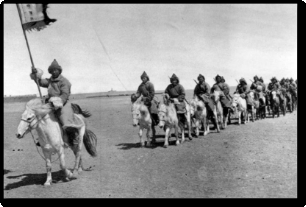

The Provincial Warlord Armies

China’s fragmented political landscape meant that several regional warlords commanded semi-autonomous armies, operating with varying degrees of independence from Chiang Kai-shek’s central government. This fragmentation is implemented in two ways.

First, more loyal regional armies—or those without a specific geographical base—are included in the general pool of Chinese units that can be deployed or built by the player. These include, for example, the Northeast Army, composed of survivors from the 1931 Japanese invasion of Manchuria, and the Northwest Army, formerly part of the Guominjun faction in the 1920s.

Second, armies with strong warlord leadership tied to specific provinces are represented in-game as Chinese minor countries. These include:

-

Kwangsi, militarily one of the strongest provincial forces;

-

Shansi, known for its resilience even under occupation;

-

Szechuan, rich in manpower and resources, offering vital strategic depth;

-

and Yunnan, also strategically positioned and critical for connections to foreign aid.

Some warlord leaders kept their forces well-equipped and trained, notably Yen Hsi-shan of Shansi, and Li Tsung-jen and Pai Ch'ung-hsi of Kwangsi. Their superior leadership is reflected in-game through enhanced HQ ratings, making their units more effective in the field.

While these warlord armies often lacked national cohesion and had varying levels of loyalty to the central government, they could usually be counted on to defend their own provinces. Their operations were typically localized and defensive, driven more by regional interests than by national strategy. In the game, I represented this behavior by assigning provincial guerrilla units and enabling the automatic deployment of additional defenders when key provincial hexes are threatened.

The Communists

Led by Mao Zedong and a cadre of skilled generals, the Chinese Communists enhance the capabilities of the Allied side—though their role is complex and often disruptive. While small in number at the start of the campaign, they have the potential to expand exponentially as the war progresses.

Centered on the Eighth Route Army and the New Fourth Army, Communist forces were officially integrated into the NRA, but in practice they operated independently—often clashing with Central Army and provincial warlord troops. To model this, the Communists are represented as a separate major country in the game: the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). As CCP units move across the map, they will agitate nearby Chinese troops, with simulated battles causing supply and strength loss to both China and the CCP. In addition, the Nationalists will be forced to garrison parts of the northwest map in an attempt to contain Communist expansion. Failure to do so will result in damage to national morale.

Although nominally part of the Allied effort, the Communists will benefit from Chinese missteps. For example, historical events such as the Changsha Fire and the Yellow River Floods—both disastrous policies initiated by Chiang Kai-shek or his commanders—boost the CCP’s Military Production Points (MPPs) in-game. These reflect the way public discontent often drove civilians into Communist arms during the war.

The CCP was highly successful in guerrilla operations, establishing base areas across northern and central China and seriously hindering Japanese logistics. I modeled this by adapting systems from the earlier Strategic Command: War in the Pacific – 1941 Day of Infamy campaign. Scripted commands automatically create CCP base areas and deploy units to inconvenient, supply-critical locations, particularly along Japanese rail lines. In addition, partisan scripts trigger the activation of CCP guerrilla units, as well as guerrillas aligned with the Nationalists and provincial warlords.

The CCP was poorly equipped compared to the Nationalist forces, with limited artillery or mechanized support. However, they leveraged their deep ties to rural populations to sustain their operations. The Eighth Route Army and the New Fourth Army became legendary for maintaining prolonged resistance despite chronic equipment shortfalls. I reflected this by allowing the CCP to build up to 18 units, but no tanks or artillery. However, their units have slightly better combat values than regular Chinese forces and can inflict demoralization effects on Japanese units.

In Part Two, I’ll delve into the composition and deployment of the Imperial Japanese Army in China, including its supporting elements, the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force, and the Imperial Japanese Navy. I’ll also explore how I’ve modeled the complex and often fragmented nature of the Chinese collaborationist forces that fought alongside—or under the control of—the Japanese throughout the campaign.