Welcome back to the Armoury. This week we are focusing on our Medieval titles. They are on sale this week, so be sure to check out games like Sengoku Jidai or the Thirty Year’s War (okay those ones aren’t exactly Medieval, technically early modern, but you get the idea. We love our pike and shot).

Instead of focusing on a particular melee or ranged weapon, we are are focusing on a concept. At the sharp end of things how did melee combat really happen? Hollywood shows us formations breaking apart and men pairing off to duel to the death, but the numbers and historical evidence don’t really support that this was how people fought. If that was the case then why did people even bother with formations? Since no one is alive from the medieval period or antiquity, we can’t just ask them how people fought.

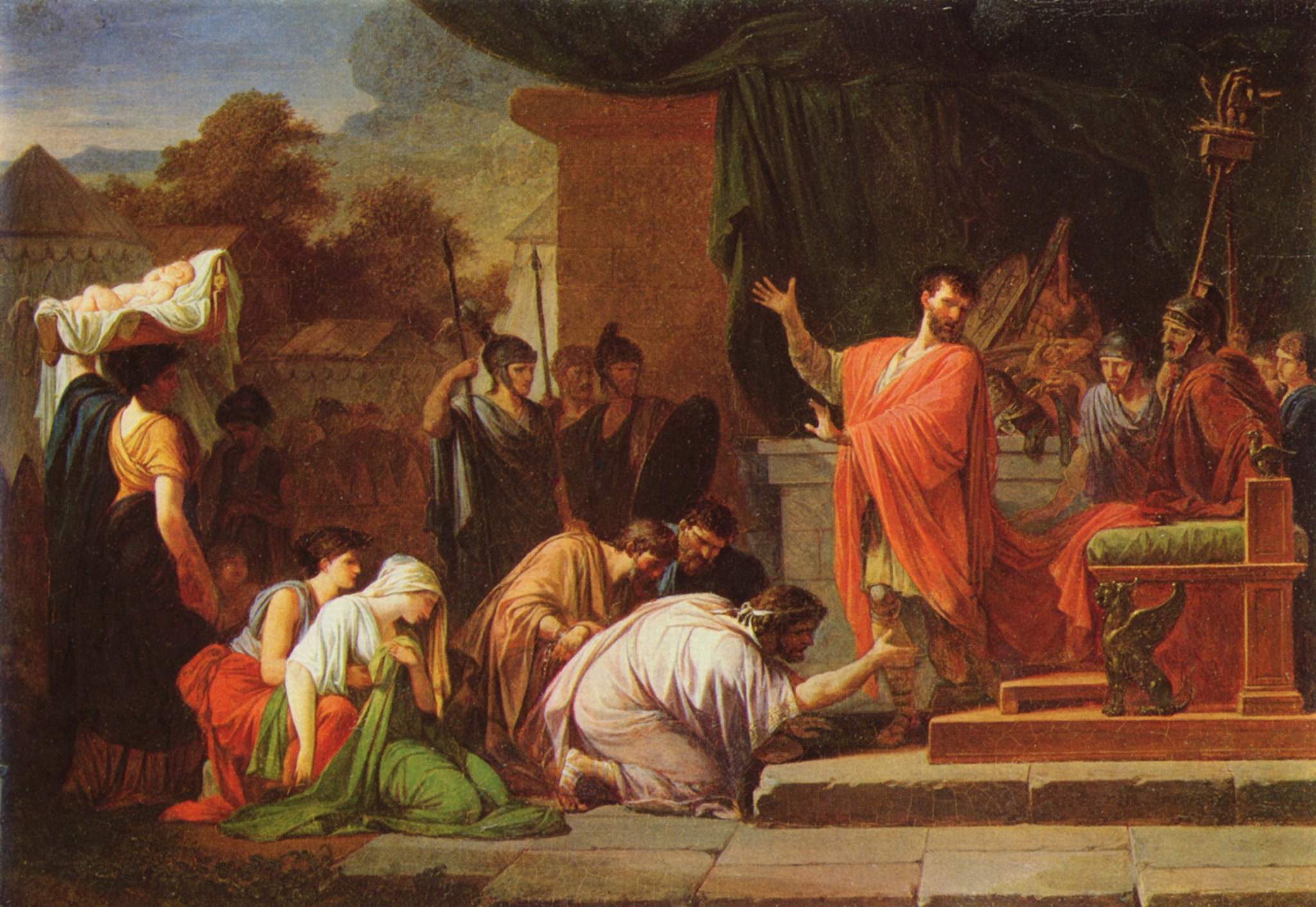

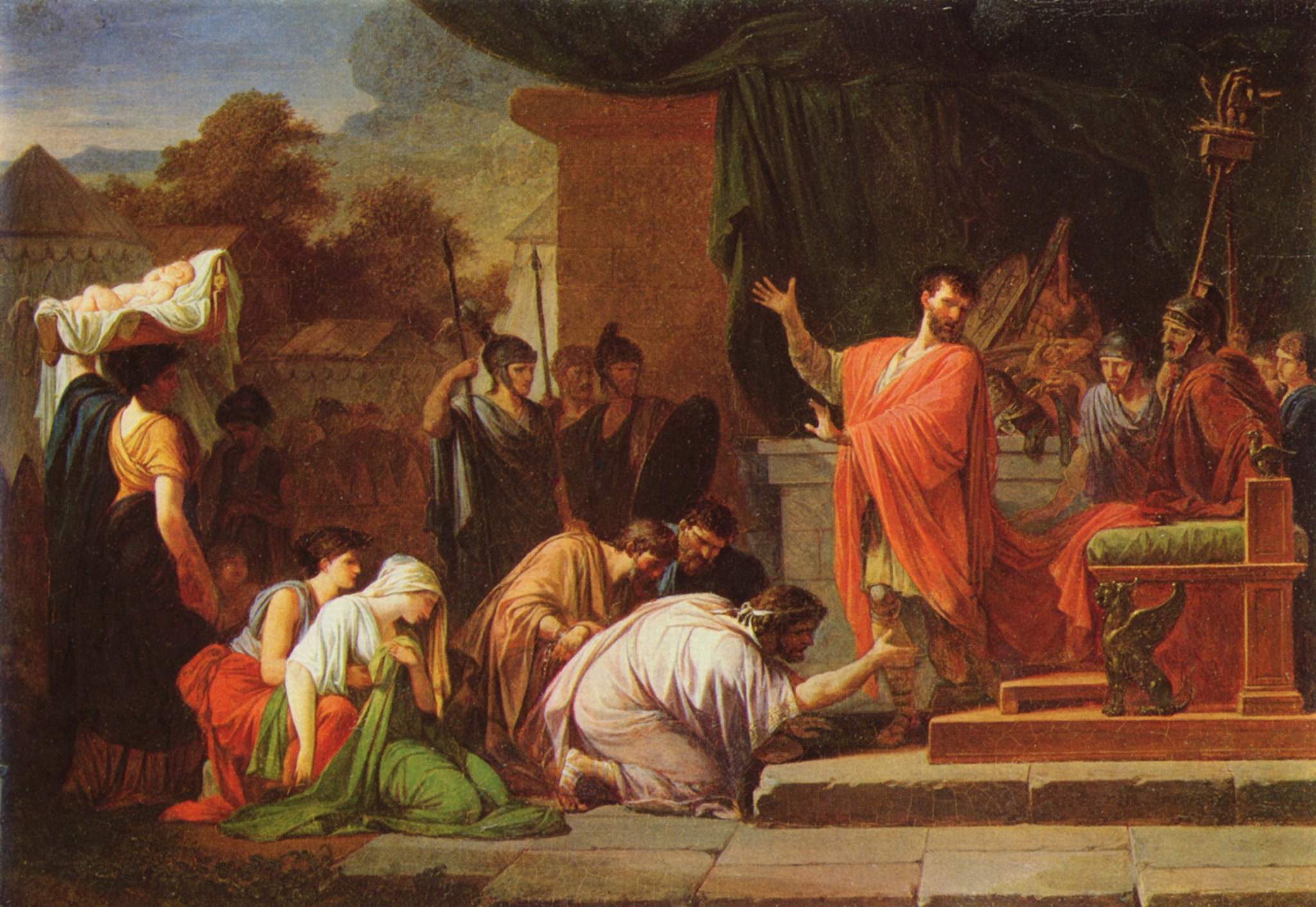

A depiction of Polybius, a key source for the Roman Republican Army

Historical sources like Polybius, Livy, or Michel Pintoin would assume the reader knew what battle and fighting actually looked like without the need to explain things. If someone from today said a squad or platoon attacked in a wedge or tactical column, would a future historian know to assume that this is with tactical spacing and bounding overwatch? Would they know that while many armies still issue bayonets they are almost never intended to be used literally as a killing weapon, but as a tool and psychological motivator on the attack? Many ancient and medieval sources don’t explain so literally how combat actually occurred. In all likelihood we will never really know how combat worked out, but we can try to make models based on the evidence we have.

Triumphal columns and arches are sometimes our only evidence for how units were ordered and equipped if no written source survives

One of the best works on this topic is “The Face of Roman Battle” by Philip Sabin. Originally published in 2000, this academic article was interested in answering just how ancient battles played out at the sharp end. At the time there was significant discourse over whether Greek hoplites literally engaged in group shoving matches, the Othismos, as a part of their way of making war. Sabin decided to focus specifically on how the Roman fought, and how you could come up with a satisfactory model that explained four key features of ancient battles.

1. Casualties were low until the route.

2. Battle lines could be pushed dozens or hundreds of yards back without a route or slaughter.

3. Battles lasted for multiple hours, how could men fight uninterrupted for such a long time?

4. The men fighting to the front were bolstered/supported by deep formations.

To summarize the article, Sabin discounted the hollywood style of ancient battles as far too bloody and exhausting. If every man broke formation and started aggressively hacking at one-another, ancient battles would be exceptionally bloody and short. He also discounted the cheek-to-jowel shoving matches where whole formations allegedly formed dense blocks and simply tried to run over the enemy.

The ancient sources like Livy or Polybius specifically talked about how individual, skilled swordsmanship was encouraged and that to properly fight, a legionary would need around 3 feet of spacing to properly move and swing his sword. We also have numerous examples from the ancient and medieval world where formations could become too dense and packed with men. This often lead to a slaughter at the front of a formation as men were forced forwards into waiting spearpoints while being pushed forward by other units behind them (Agincourt is a stellar example of a crush like this).

Sabin proposes a model of periodic clashes between formations. In short, a good ancient or medieval commander would put his best men at the front and rear of a formation. The men at the rear would discourage running, and the ones at the front would do the lions share of fighting. As two formations neared one-another ranged weapons like pilum, axes, or darts would be thrown. What we would now call junior officers, the centurions or tribal chieftains, would need to build up enough confidence and energy in his men at the front to actually close the distance and engage the enemy in melee combat. The rest of the formation would continue to provide support with missile fire, words of encouragement, and supporting wounded or exhausted men back from the front-line.

Formations periodically breaking contact and being pushed back would explain the hundreds of yards of movement seen at battles like Pydna

After the frontline fighters were exhausted a natural lull would see both sides separate, reorganize, get a breather, throw more missiles, and then surge back into action once a centurion or particularly brave soldier had psyched his men up enough for another try. This explains why the “junior officers” thought history have such appalling casualty rates. A brave centurion has to physically lead his men forward to actually achieve victory.

As a battle wore on, the untested men in the middle of a century or cohort might grow anxious, or have to take over more of the fighting duties as the natural killers at the front were either killed, exhausted, or had to retreat due to wounds. This attrition, the physical and mental exhaustion of the men involved in the battle, was a crucial factor in units losing effectiveness and routing. If a formation was turned and flanked the psychological panic and horror at seeing enemies coming from an unprotected direction would have been horrifying.

The natural psychological reluctance to close with another person and fight them with a sword and shield cannot be overstated. People have a very strong aversion to being stabbed, which also helps explain why the pike block could be so useful. When Philip and Alexander conquered Greece and Persia with their Sarissa-armed pikemen, they had given their soldiers a tremendously useful weapon. A pikeman can bravely push forward thrusting with his pike without exposing himself to danger from a melee combatant. Unless facing a similarly armed phalanx, a pikeman can advance with confidence knowing his foe will find it almost impossible to close within melee range of him.

Alexander's defeat of Darius, prominentley featuring massed rows of sarissa's in the background

It’s likely no accident that across the globe, before the complete dominance of gunpowder, multiple cultures adopted pike blocks as one of the last large-scale melee infantry formations. The European had the Tercio and Pike and Shotte, the Japanese had Long Yari and Teppo, the Ming dynasty had a mixed Pike and Sword formation called the “Mandarin Duck”.

When two pike formations clashed, the push of pike could turn into a bloody morass that was seldom decisive

Now this is a good general working model for how melee combat worked, but we need to be careful. War takes an infinite number of forms and there are plenty of exceptions that a good commander would recognize. A Roman armed with a gladius and shield needs room to fight and manuever, and has his throwing spear to help add to a battle even if he isn’t directly in melee combat. A pikeman however needs far less space to thrust with his pike, and their formation is far more dense and prone to collapse if flanked.

.jpg)

A surviving scutum shield from Dura Europos. Being made of wood and leather, intact shields are exceptionally rare finds

If we can take a universal lesson about ancient and medieval warfare, it’s that human beings are adverse to closing with the enemy without psychological confidence. This is arguably one of the greatest things about armour, not just its actual protective properties but the confidence it engenders. This model also does a great deal to shed light on how ancient and medieval battles could be so decisive. Well trained or veteran troops, confident in their leaders, could decisively charge in knowing that the more they attack, the more they get stuck in, the sooner it would end in victory. Real mutual bloodbaths occurred when both sides, confident in success and skilled in arms, traded blow for blow in destructive mutual bloodletting's.

The Battle of Towton was an exception to most battles, where both Lancastrians and Yorkists took very heavy losses

The introduction of gunpowder played a huge role in changing the nature of how battles were fought. Indecisive battles with heavy casualties on both sides became a far more regular outcome. Sieges and fortifications also became far more elaborate and expensive to wage and maintain. But that is a story for another day.

If you are interested in this sort of literature I would highly recommend you give “The Face of Roman Battle” by Philip Sabin a shot, it’s a quick read and is tremendously insightful. As already mentioned, our older Medieval titles are currently on sale on the Matrix store. Happy war gaming everyone.

.jpg)